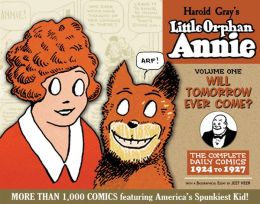

Like IDW's ongoing DICK TRACY reprint project and Fantagraphics' THE COMPLETE PEANUTS series, IDW's exhaustive cataloging of the adventures of America's favorite orphan (now there's an ironic turn of phrase...) bids fair to be on my "pull" list (or, in this case, my "pick up gingerly and deposit the large item carefully into the box" list) for a long time to come, economic vagaries permitting. It may even top those fine efforts, since it enjoys the added feature of a legitimately interesting and challenging series of essays by comics scholar Jeet Heer that, when they are finally fully compiled, should shake up a lot of what comics fans think they know about Annie's creator, Harold Gray, and the singular worldview that informed his work from day one.

This first volume reprints daily strips from Annie's debut in August 1924 through October 1927, plus a handful of Sunday pages. (Most of Gray's Sundays during this period were standalone gags; the editors reprint a few of these, plus a handful that actually tie in with the ongoing daily narrative.) For those, like me, who got most of their previous exposure to Gray's spunky, two-fisted waif from the massive Arlington House volume that only reprinted strips from the period 1935-1945, Gray's earliest strips will seem crudely over-elaborate, the work of a modestly talented artist trying to distinguish himself from the style of his ex-boss Sidney Smith (whom Gray assisted on THE GUMPS) by punching above his weight. It doesn't take long, however, for Gray's "natural" style to reveal itself. The cycle of "hard-knocks adventures among the common folk" linked to brief but memorable reunions with Daddy Warbucks, the clipped sentences, the occasional "pause and reflect" strips, and the fourth-panel philosophical ruminations manifest themselves with similar swiftness. So, too, do Gray's odd touches of amoralism. We're still some time away from the introduction of Warbucks' notorious sidekicks Punjab and The Asp, but this somewhat less sinister Warbucks is still capable of using two toughs to "encourage" a French doctor to leave his cushy practice and come to America to fix Annie's paralyzed legs. Likewise, Warbucks' snooty wife, who'd earlier treated Annie like dirt and abandoned her husband to take up with a suave European swindler, returns to the storyline poorer but wiser and genuinely contrite -- she even looks like a nicer person, facially speaking -- but no sooner has she reformed than she's disposed of through the impersonal medium of a storm at sea that swamps the Warbucks yacht.

Oddly, when they first meet, Annie has better diction and grammar than Warbucks, the self-made war profiteer who's initially characterized as a diamond in "rough" of razor-wire consistency. As time passes, however, Daddy acquires polish, while Annie begins dropping her "g"s with regularity and otherwise using the lower-middle-class style of speech that she'll employ for the rest of her career. Both Annie and Warbucks are obviously great, sympathetic characters from the first moment, and I'm perfectly willing to amend my well-known affection for "feisty young male characters" and invite Annie to join the club. (She can room with Darkwing Duck's Gosalyn Mallard, a very similar character -- to state the glaringly obvious.) Aside from these two, Annie's dog Sandy -- who debuts as a puppy (!) and undergoes a rather dramatic "ear-bob" during his physical development as an adult -- and the Silos (the kindly farmers who are the first of many strangers to take in the Warbucks-less Annie), the ANNIE cast at this stage is still pretty skimpy. Give Gray time, however.

Heer's essay on Gray's youth and early work argues convincingly that Gray, at least at this stage of his career, was far more of a "progressive" Republican than the later hard-shell guy who despised FDR. He overstates his case in places, but, more importantly, he makes clear why Gray was so opposed to the New Deal later on. If Gray hated anything, it was hypocrisy, pretense, and putting on airs; the quintessential Gray walk-on character, the neighborhood busybody, is very much in evidence from the start of ANNIE. Rather like H.L. Mencken, Gray hated FDR as the consummate pretender who purported to serve the common man by in effect buying his vote through a national elaboration of the old-fashioned ward boss strategy. (The pork-laden "stimulus package" passed a few days ago is merely an updated version of this strategy, of course.) Since Gray was among the most sincere and least ironic of comics creators, his rage was fueled by a genuine sense of disillusionment. Like Charles Dickens (to whom Heet compares Gray in the intro to Volume 2), Gray believed that reform began not with the stroke of a bureaucrat's pen but with a change of heart. Unfortunately, Gray's very sincerity led directly to his greatest failing, a lack of humor. There are a number of slapstick gags in the early strips, and Annie occasionally serves as her own worst enemy by committing such small-beer sins as eating too many bananas, but the laughs get fewer and farther between as the strip moves forward. Well, at least Gray knew what his strengths were.

I should be getting on to Volume 2 soon. These are DEFINITE keepers.

No comments:

Post a Comment